When we need to produce something quickly and efficiently, a natural reaction is to break a process into certain tasks and then repeat the same task multiple times on multiple products before moving on to the next step in the process.

As an example, if you ask people the best way to quickly and efficiently fold and stuff envelopes with paper, the majority of people will suggest folding all of the paper first, then putting the paper in each one of the envelopes and then sealing all of the envelopes — this intuitively feels like the best way to complete a process.

This is an example of batching — we can see batching in manufacturing and in service delivery from baking batches of bread required by a bakery in the morning, to approving team expenses once a week to waiting until you have X forms to process before processing them.

Unfortunately, our intuition that batching is best is often wrong and leads to poorer quality, longer wait times for customers and increased costs.

This is often true in factory-based manufacturing, healthcare and in public service administration.

I ran an experiment with 48 delegates for a set of training courses I recently delivered, in each group I put together a production line made up of 3 volunteers to produce paper aeroplanes. The aim was to produce 18 aeroplanes as quickly as possible (to quality) using batch production (6 per batch).

Across the groups the average time to complete 18 aeroplanes was 12 minutes, often it was taking over 5 minutes for the customer to receive the first plane!

The other issue with this process was by the time the customer received the plane, there was around 10 “aeroplanes” in production.

Why is this a problem?

If there is an issue with the quality of a plane that hadn’t been identified internally, potentially up to 10 planes would need to be “re-worked” causing significant delays, cost and frustration all across the “production line”. For the customer; they have been waiting around 5 minutes to receive a paper aeroplane and it’s still faulty!

So, for the customer this process isn’t good, they have to wait a long time and potentially have to wait even longer for the defect to be resolved.

For the business, it is not good news either. If the company only gets paid when the plane is delivered, then they have to wait a long time and even have to finance lots of inventory (in this example 10 paper aeroplanes).

Having lots of inventory causes problems:

- You need to store it (big warehouses, WIP drawers) and keep it safe (GDPR!!)

- You need to find it again when you are ready to work on it

- You need to pay for it (cash flow issues)

- You don’t know you have a problem with a process until you have worked on lots of items

- It goes out of date (obsolescence) and;

- Customers want to know where their plane is (failure demand)

There is another way, and its called flow, or more specifically one-piece-flow.

Flow is when work “flows” from one part of a process to another with no waiting, the ‘piece of work’ never stops moving until it is delivered to the customer.

The mantra of one-piece flow is:

“Make one, Move one”

This means there are no queues, no piles of work and any problems are seen straight away.

Flow is about reducing the “batch size” as much as possible, the ideal is one-piece flow.

When you try to explain the idea of working on one piece of work at a time with no buffer to managers, it often sends a shudder down their back in horror — “how could that possibly work here?”

Firstly though, the real test is, can it help us make paper aeroplanes more quickly, more efficiently and to better quality?

To find out, I repeated the exercise with the delegates on my training course, the process was the same except instead of having a batch size of 6, it was now 1 (i.e. one-piece flow).

What happened?

The customer received the first plane within 26 seconds (under batch it was around 5 minutes)

All the planes were completed within 5–6 minutes (under batch it was 12 minutes)

This means that the lead time to produce the first plane was reduced by over 90%, if the customer spotted an issue upon delivery, how many planes were being worked on at any one point? (the answer is between 1 and 2, not 10).

Also, the overall time to produce the paper aeroplanes reduced by around 50% (essentially productivity has doubled).

Another advantage of this process was the inventory or WIP levels, under batch production there was an average of 10–12 planes in production at any one time, under one-piece flow it was between 1 and 3 (normally less than 2).

Achieving the ONE in one-piece flow in the real world is complex, hard work and sometimes not even achievable — however having the aspiration to get to one-piece flow and taking practical continuous improvement steps to get there, will help you:

- Reduce costs

- Reduce lead times

- Reduce WIP

- Improve productivity

- Improve quality

- Increase customer satisfaction

What are the barriers to achieving flow?

Unfortunately, there are quite a few, however working systematically on reducing the impact of these barriers will help you achieve each of the outcomes above.

The barriers:

- Quality problems requiring re-work

- 8 wastes and Non-Value-Adding activity

- Work requiring approval

- Handoff’s between colleagues and locations

- Lack of colleague skills and communication

- Bottlenecks (poor work balancing)

- Resistance to change

- Batching/ piles of any kind (e.g. emails, WIP/BF folders, stacks of claim forms)

- Long set up times (e.g. login times to get into a specific IT programme)

- Prioritisation rules and changing management priorities

Quality problems requiring re-work

When something is produced that doesn’t meet the specifications determined by the customer, it creates a cost through re-work, loss of reputation, complaints, scrap and opportunity cost (what could the agent have been doing instead?).

You can not operate in a state of flow if you are constantly re-working and fixing problems. Therefore the first step needs to be to identify the causes of quality issues and fix them, tools such as FMEA and root cause analysis will help

8 wastes and Non-Value-Adding activity

Any of the 8 wastes (waste of; transportation, inventory, motion, waiting, over-processing, over-production, defects, skills under-utilisation) or undertaking non-value adding activity will prevent perfect flow from happening. Therefore, you need identify the sources of waste and address them, using Value-Stream Mapping and other tools.

Work requiring approval

If your colleagues need their work to be approved by a third party (e.g. a team leader), it creates delays,undermines trust and adds to supervisory burden. Whilst sometimes necessary, you should try to reduce the number of tasks requiring approval (e.g. by taking a risk based approach and investing in additional training).

Handoff’s between colleagues and locations

When work is passed on it increases the risk of queuing and increasing WIP, but also increases the risk of many of the other 8 wastes. When work is handed over to another person in the process, they are likely to review the case to familiarise themselves with the details and then start work (duplication of effort / over processing). If there is a variation of working practices this will add additional delays.

Lack of colleague skills and communication

If colleagues don’t understand the whole process and don’t have a high degree of skill in their job, it will lead to inconsistency of work (quality and timing). Therefore, you need to provide the right level of training so that colleagues can do the job ‘right first time’.

You need to make sure that there is the right communications process in place so that problems that are spotted can be flagged immediately, and ideas for improvement are supported and implemented.

Bottlenecks (poor work balancing)

The phrase “a chain is only as strong as its weakest link”, perfectly sums up the idea of bottlenecks and achieving flow.

As an example, If you have a 3 step process;

- Step 1 can produce 10 planes per minute (6 seconds each)

- Step 2 can produce 2 planes per minute (30 seconds each)

- Step 3 can produce 60 planes per minute (1 second each)

What is the situation after 10 minutes?

Step 1 has produced around 100 planes, however step 2 can only produce 2 planes per minute, so they have produced 20 and passed those 20 planes onto step 3 who can deal with that level of work in 20 seconds (but were employed for 10 minutes — 3% value adding time!).

If we look at the inventory situation, its not a pretty sight. Because step 1 has produced 100 and step 2 has only done 20, there are 80 pieces waiting to be worked on.

Whilst this is an extreme example you can see that having a bottleneck stops flow from happening and contributes to many of the 8 wastes.

One of the ways to reduce the impact of this is to smooth out the tasks in each job role, so each task takes about the same time. This approach means that waiting time and inventory is reduced and so is the pressure on the bottleneck.

Another way to address this issue is to focus all improvement effort on the bottleneck (or limiting factor), after all that is the only way you will be able to produce any quicker. If you improve step 1 and increase productivity from 10 per minute to 20 per minute, you are actually increasing the inventory and pressure at the bottleneck, leading to quality issues.

Resistance to change

Most people don’t like change whether that’s front line colleagues or managers, however:

“if you always do, what you always did, you will always get what you always got”.

One of the main barriers to change is a preference for the status quo, operating on the front line with limited “power” can make implementing CI led improvements difficult.

Two ways to combat this inertia to change are:

- Start small — focus on quick wins or “marginal gains” that don’t require investment, major upheaval or training but simply make things better. Lots of small changes adds up to a culture change

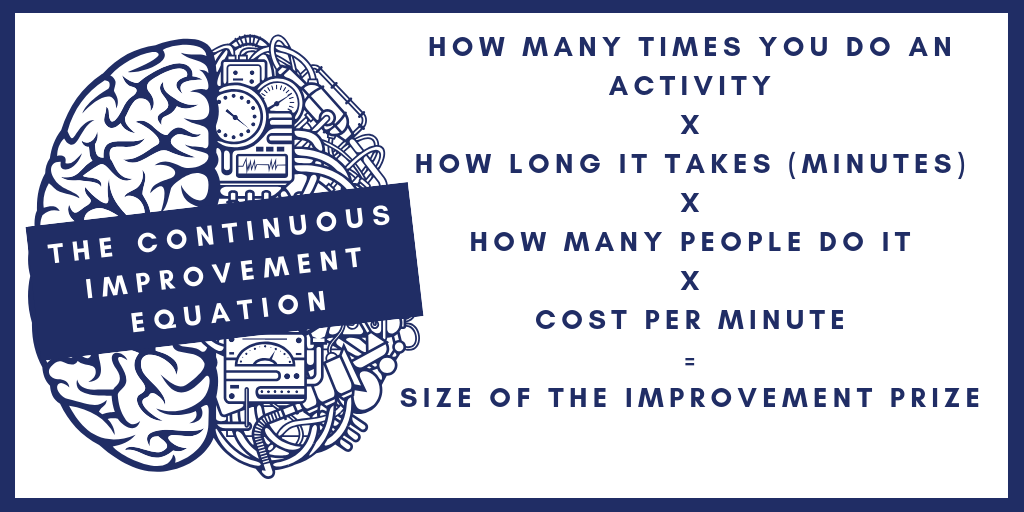

- Use data — if you don’t have data you are just another person with an opinion, if you capture data about a problem (i.e. using the CI equation), you are more likely to be able to provide a compelling argument that speaks the language of management.

Long set up times (e.g. login times to get into a specific IT programme)

When it takes a long time to switch or changeover between tasks, it promotes batching, focusing on one task only and creating buffer inventory (“whilst I am logged in I may as well process the next 30 pieces of work”).

In a service or processing environment, the types of setup might be log in times, changing desks or even recruiting and training a new colleague.

Key to achieving flow is reducing long set up times, so this might be investing in digital technology to do “single sign on” and reduce the time required to go onto a different system.

In other cases, the key is to recognise what a “changeover” is and then standardise and improve each aspect of the changeover process.

There is a whole training course that can be dedicated to this concept, which is often referred to as SMED (Single Minute Exchange of Dies). One of the most famous examples of this technique is in Formula 1 and the “changeover” of tyres.

A good place to start is to look at where changeovers happen in your processes and then use the CI equation to identify opportunities for improvement.

Prioritisation rules and changing management priorities

We have all been there — changing management priorities on a regular basis. Ultimately if everything is a priority, nothing is a priority. To achieve Continuous Improvement and flow you need to make sure that as much as possible you establish a clear, understandable goal and everyone can unify behind.

Conclusion

In short, achieving a state of flow is difficult.

However systematically working through the 10 barriers to flow will lead to incremental improvements which are individually achievable and collectively will increase quality, productivity and your ability to deliver on time for your customers.